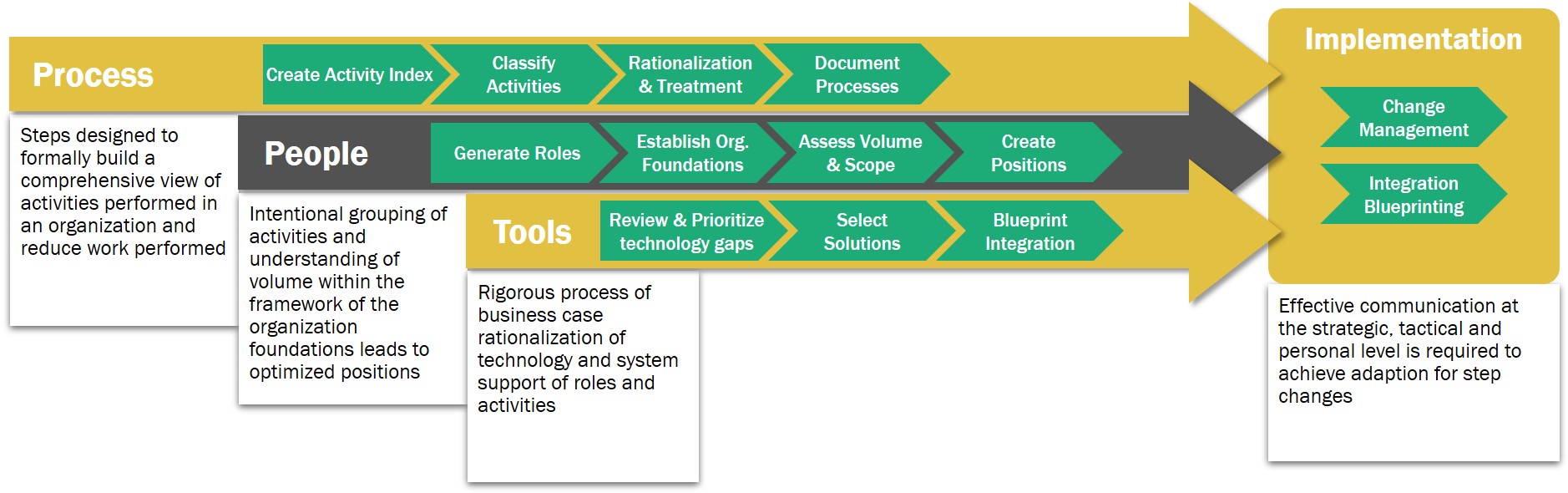

Welcome to the third installment in our series, “A Process for Business Transformation”. If you have not done so already, you can read our introduction article here, and our second article, outlining Step 1 through Step 4, here. In these previous installments, we addressed the importance of understanding the value-add activities required to run a business, in other words, “what we need to do”. Having established the base understanding of the activity environment, this transformation is ready to take its next steps.

In previous steps, the activity review sought to improve business performance by identifying opportunities that reduce the volume of work or improve how work is performed. This allows leadership to define the demand for labor and competencies across the organization. Picking up where we left off, we arrive at the next common mistake we see in transformations that yield less successful results for the organization: a focus on positions and a lack of consideration for redefining roles.

Before making our case for re-evaluating roles and positions, however, let us standardize the definition of the terms themselves. We often see the terms “role” and “position” used synonymously, but there is an important distinction between the two which needs to be established before moving further. For the purposes of this discussion, and recommended for any organization:

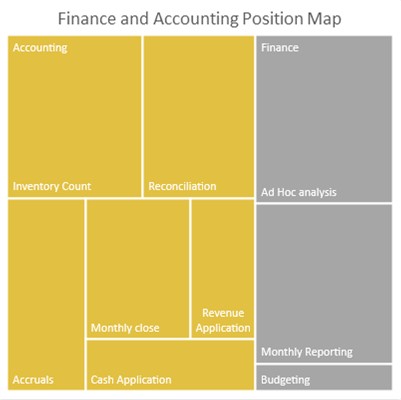

• A Role is defined as a collection of related activities. This relationship can either be through common competencies and skill requirements or through process.

• A Position, on the other hand, can be composed of one or more roles as determined by scope and activity volume (and will be discussed in greater detail in Step 7).

This phase of the Process for Business Transformation is designed to facilitate a transition from “what the organization does” to “who does what”. People are at the center of every business transformation, but we often see too little rigor put into the redefining of roles and positions. Without process discipline to address roles, structure, and positions, organizations will struggle to fully realize the returns from transformational activities. Opportunities for the organization in this phase focus on a few key areas:

- Effectively consolidating activities to produce roles

- Managing scope of roles within the boundaries of the organization structure

- Balancing roles and scope to efficiently define positions

Outside of the immediate targeted improvement areas listed above, the act of linking people to activities opens a host of longer-term benefits to the organization. Among the more interesting is establishing a mechanism to reconcile the demand for certain competencies with the supply of those competencies within an organization. This can only occur through the link between activities that need to be performed and the roles that will perform them.

Step 5. Generate Roles

One of the most overlooked and least understood methods for effectively improving efficiency within an organization is the process of re-evaluating existing roles and responsibilities. Roles are critical to the realization of transformational improvement as they act as the link between required activities and your organization’s human capital. For now, the goal of this step is to transform a list of activities into a list of roles. Each activity needs to be listed, evaluated, and then grouped to correctly define a role. Below are common pitfalls and best practices related to role generation.

Common Pitfalls

Perhaps the most pervasive pitfall we see is creating a position before a role. When the process runs in reverse, the organization is put into a situation where the role that was created is searching for activities and responsibilities. It is in these situations where the risk of creating unnecessary roles or extraneous activities is highest. Roles should always be built from activities, not the other way around. This is commonly a result of existing organizational structures, instead of on the actual necessity of activities. Another common pitfall comes in a lack of designed standardization. Standardization across business units is a popular goal of business transformations but is often stalled by efforts to standardize a position rather than the roles. If you are finding it difficult to standardize a global organizational definition of a role this can often indicate a lack of process standardization and will need to be addressed. A lack of understanding or consideration of the supporting roles and players effecting a single role’s commitments only serves to create confusion within the organization.

Best Practices

Role generation and process improvements are closely tied. To expedite the transformation process, avoid back tracking and develop each role to the fullest extent possible. Role generation should run concurrently with process reengineering initiatives. The goal of building any single role is to gain efficiency in process or activities performance by grouping like activities to minimize output handoffs. A quick way to gauge your effectiveness is to count the cross-functional role paths in your process (made much easier with cross-functional flow charts or with a process flow RACI). Another effective way to consolidate activities to roles is by combining roles with similar competencies. This can be pulled directly from your activity index. Finally, successful transformations remain aware of their role count; while you need to create enough roles to cover required activities, it is surprisingly easy to end up with a massive number of roles in your roster.

Step 6. Determine and Establish Organizational Foundations

Business transformation initiatives start at the ground level, including the organizational structure. Before continuing the Process for Business Transformation, you need to answer the following questions, independent of bias and the existing structure:

• What is the foundation of your business?

• Is your company geographically focused or product or service line focused?

• Should you be organized as a matrix or a straight organization?

• Should roles and functions be centralized or decentralized?

The answers to those questions and other decisions made in this pivotal stage can enable or restrict the ultimate performance of the business. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on some key considerations for evaluating those options during a transformation.

Common Pitfalls

A major pitfall we see in selecting a foundation for an organizations structure is an appreciation that each business is unique and what works for one organization will not always work for another. While benchmarking satisfies a curiosity, it can be damaging if used as a shortcut. Similarly, related to this pitfall is a bias towards the current state. It is important for transformation teams to understand the investment many have in the established organizational structure e.g. career paths, mentors, and goals. Transformation teams need to maintain an objective lens when reviewing structural options. One of the most pervasive traps in selecting an organizational foundation is making it too complex. Maybe while recently scrolling through LinkedIn you found an HBR article espousing the benefits of a Tensor structure (a multidimensional matrix structure, and yes, it is as complex as it sounds) and you liked the idea of it, but that doesn’t mean you need one. In our experience, defining clear paths of accountability yields more benefits than adding complexity to your structure.

Best Practices

If I had the ability to institute one un-breakable rule of organizational design, it would be to keep the customer at the center of any design discussions. This does not mean you have to mimic your customer’s structure (if you are in a B2B business), but the structure and nature of your customers should have the most significant impact on your structural decisions. The most successful organizational designs we have implemented were those that kept customers at the center of the process. Customers are of critical importance to defining organizational foundations and the holistic business strategy. If you ignore strategy in the organizational design, it makes it impossible to execute strategy and the negative impact can take various forms. For example, if your organization’s goal is to be the quickest to respond to your customer and their issues compared to your competitors, it may make more sense to decentralize key decisions in order to be more agile and responsive. On the other hand, if your strategy is to be the most cost-competitive it is often easier to achieve this through a stronger, centralized structure. Regardless of the structural foundation selected, it is critical that paths of accountability are well communicated, understood, and reinforced; this will get you further than any other aspect of organizational design.

Key Organizational Priorities

- Industry practices

- Business lifecycle (start-up, mature, etc.)

- Business strategy (Organic vs Acquisitive growth)

- Segmentation of the customer base (Regional, National, Global)

- Customer buying structure; Local vs Decentralized, Electronic vs Physical

- Agility vs Control

- Centralized vs De-Centralized

- Local Support vs Remote Support

- BU interoperability

- Business Processes

- Ownership structure (Private vs Public)

- Regulatory Environment

Key Structural Forms

- Flat

- Linear

- Matrix

- Tensor

Key Organizational Decisions

- Geographic vs Product / Service Line

- Functional focused structure

- Value Chain oriented

- Standardization vs Specialization

Step 7. Assess Volume and Scope

After defining the foundation for the organizational structure, the process turns to defining the volume of activity across the organization. The goal of this step is to define an expectation of personnel time that will be demanded by the business. A truly optimized organization must consider the volume of activity that will be undertaken by any individual role with respect to the scope of that role. Although this is often an arduous task, it is perhaps the most critical piece to designing an organizational structure that minimizes costs while not overburdening personnel. A critical component to assessing activity volume is selecting the basis of activity. The more tactical the activity, the simpler the activity metrics will be, e.g. number of invoices processed or number of POs created. As activities become more strategic, the basis of activity measurement will become far less direct and more difficult to measure, e.g. number of products or customers to assess sales activity burden.

There are several methods that can determine the time requirements for an activity and the maturity of the data environment. Time and budget will inform the most appropriate method to assess the activity levels. Activity measurement will often include a blend of surveys, volumetric data analysis, and more advanced techniques like process mining. This is done by utilizing the organization’s available data to determine duration of specific tasks. Once a good understanding of the volume of work is established, organizations must then determine the most efficient and effective method(s) to define the scope of roles that will perform the activity. For example, does the activity demand a single role to cover Brazil, or should that role’s scope cover Brazil and further extend to the entire South American Region? With the activities a role performs defined in Step 5, the scope of a role becomes the primary lever to drive full utilization of personnel.

Common Pitfalls

While interviewing every individual in an organization is not practical, it is often required to establish activity levels. The most common issue we see, often found well after the fact, is an underestimation of time required to perform an activity. This is a result of several factors. First, activity surveys will be completed by the wrong layer of the organization. Remember back when you started a job and seemed like the manager had little clue as to how long things took to complete. That issue remains and if it finds its way into your improvement process it results in under- or over-staffed organizations. You should include key personnel that can provide an accurate assessment of activity in all activity surveys. Secondly, a lack of utilizing data to confirm survey results can cause an underestimation of time required to perform an activity. Most organizations will not have system data logs for every activity the organization performs. However, a lot will have data close enough to be directional and highlight gross over or underestimation. To use a Russian proverb, “Trust, but verify”. Outside of data acquisition, the second most common mistake made in this step is attempting to pre-define the boundaries of the organization structure. While the resulting structure needs to make sense considering the overall business environment, we have seen many efficiencies lost through trying to fit into a preconceived notion of organizational boundaries.

Best Practices

In defining activity volume and scope, the best results come when you keep your eyes to the future. Activity data may need to be amended but remember a key purpose of transformations is to change how organizations work, hopefully reducing the time demanded to complete processes (through rationalization, automation, etc.). Transformations will never be fully optimized at the time of implementation. In fact, seeking that end will only cost delay, money, and frustration. As such, a best practice for organizations to take is to establish activity review and scoping as a continuous improvement processes. Establishing an activity management process will yield gains far past the transformation project, and flexible scoping will allow businesses to react quickly to an ever-evolving business environment.

Case Study

Situation: A $70M industrial services organization was struggling to meet the profitability of their competitors and internal targets. They operated in the US market and in twelve regions, each with a manager overseeing field technicians.

Issue & Solution: During the assessment phase, we discovered that the twelve-region structure and regional manager roles had been put into place without a defined set of responsibilities, and the number of regions created was based on traditional organization metrics. After defining what activities the organization needed, the role to perform them, and the volume of time required, it was found that the organization had twice as many regional managers as was needed to perform the work. The organization was restructured to six regions, reducing the number of managers by the same and simplifying the internal order-to-cash process.

Step 8. Creating Positions

We have finally reached the point of the transformation process where positions are created. The goal for this step is to incorporate roles into positions in a way that maximizes the utilization of each individual in the organization. This includes both consideration of total time requirements and efficiency in process. Some roles will share common information requirements that make them a natural fit together, while others may not seem like an ideal fit. As the business environment becomes ever more dynamic and cycles continue to shorten, organizations need to be able to adapt and respond quickly. It’s for this reason, that we promote the concept of management by roles. The key enabler of role management is multirole positions. A constant issue we have encountered is a desire for standardization within an organization coming up against the unique business requirements and different pieces of the business experience. The common result is to create exceptions upon exceptions eventually reaching the point where the benefits of the organizational transformation are all but lost. Role standardization (separate from position standardization) allows the flexibility needed to both standardize the organization as well as respect unique business needs. Another common problem we encounter are organizations struggling to improve KPIs, such as Span of Control, Layers, etc. This issue is most often seen when attempting to apply a standardized structure to smaller markets, resulting in low spans of control. In these markets KPIs can be improved through multirole positions.

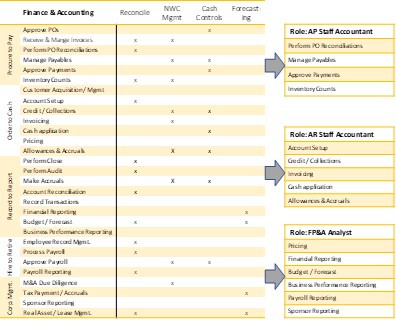

The example above describes a role that manages both accounting and finance roles for an organization. This view allows management to assess the responsibilities and role allocation of a position that is created.

Common Pitfalls

Organizations hire individuals to fill positions, but positions should never be created for an individual. Rather, the roles needed should be explicitly stated and consolidated into a position. Then, and only then, should an organization seek to fill that position with a specific individual. A second pitfall happens when organizations create positions with too expansive or conservative a scope. In other words, they create positions that either have too much to do or too little to do. While it may take some adjusting to determine the proper amount of scope in a given role, organizations must constantly be seeking to “right size” scopes to the position using the position tree map above. The final common mistake we see when advising clients is indiscriminate matching of roles into positions. There are certain roles, that for efficiency would make sense to consolidate to a single position, however for control purposes it may not make sense to do so. For example, it may seem logical to combine sales with commercial roles, but it may not make sense for sales roles to also have absolute control over the commercial terms of a deal.

Best Practices

After consolidating roles efficiently and effectively into positions, the most successful organizations will establish a process of continual evaluation of activity, scope, roles, and positions. Activity volumes will change throughout the course of business, either directly from business activity or through continuous improvement plans. The ability to quickly consider both real and prospective changes in activity allow these organizations to both respond quickly as well as improve planning. Finally, linking inputs all the way through the process, enables personnel resource planning to be taken to the next level. You have likely seen skills matrices before, but these often only provide the supply side of the equation for personnel planning. By defining competencies at the activity-level, organizations can use the transitive nature of the process to define the demand side of personnel resourcing.

The process allows for the assessment of organizational fitness with respect to the needs of the business.

Conclusion

The key to making a business successful is to make the people in that business successful. Our process for business transformation seeks to provide this success through role clarity, ease of interactions, and ensuring the skillsets in the right positions. In order to achieve these successes , we have found in our experiences and work it is best to start with activities and work towards individuals; working in the opposite direction can lead to confusion and a suboptimal business organization. This portion of the process starts with a link to process and activities, transforming activity into roles. Once roles have been created and standardized it is important to define the possible basis for the organizational structure and then assess activity levels within the potential boundaries of the organization; roles can then be consolidated into positions. From this process transformation, leaders are provided three levers to improve business performance. The first is in the efficient consolidation of activities into roles. The second is manipulating the scope of roles to drive utilization. Finally, the third is efficient consolidation of roles into positions.

In our next installment, we will address the considerations for technology, systems, and tools in “A Process for Business Transformation”.

Read the final article in this series: Enabling Process and People with Digital Transformation

Download this Article as a PDF